BY NATALIE MOORE, Capital Region Living Magazine –

On a recent late spring evening—a Tuesday, mind you—Downtown Schenectady was humming: Trivia was in full swing on the patio of Katie O’Byrnes, a steady stream of theater-goers filed into Proctors for opening night of Harper Lee’s To Kill A Mockingbird, and the tables were full at The Nest, one of the Capital Region’s trendiest new restaurants. The recently opened and much-talked-about Van Gogh: The Immersive Experience exhibit at the Schenectady Armory was closed for the day, but would reopen the following morning to swarms of art lovers. Just outside of downtown, at the state-of-the-art Mohawk Harbor compound, a pair of kids rolled down the hill leading to the harbor, while diners of all ages enjoyed drinks at waterside restaurants Druthers Brewing Company and Shaker & Vine, and a gaggle of young women relaxed in The River House apartments pool.

If you took someone who lived in Schenectady in the ’90s and then moved away, and dropped them in this scene, they probably wouldn’t believe their eyes. “Whether it’s Union College alumni or people who used to be in Schenectady 20, 25 years ago, when we bring them back, they’re floored,” says David Buicko, president and CEO of the Galesi Group, the Schenectady-based development company that’s responsible for Mohawk Harbor as well as many downtown projects. “It’s shocking to them, because they still think of Schenectady in the past.”

All Capital Regionites probably have at least some idea of Schenectady’s ups and downs, which have been more extreme than those of any other city in the region. But those who lived in the city in the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s remember vividly the time before the “downs,” when Schenectady’s well educated residents served on city and nonprofit boards, shopped in downtown stores, and raised their families. “We were free-range kids,” says Schenectady native Bill Gallagher of growing up in the late ’60s and ’70s. “We were always playing outside. We’d walk home from school every day up Eastern Avenue and had multiple stops—we stopped at two corner stores, the fire house, the shoemaker, a pub (we did not drink), and there were a couple office people that we would wave to in the window and they would come out and chat with us. There were just so many nice people.” To fully appreciate that idyllic time, however, it’s important to go back even further, all the way to the origins of modern-day Schenectady: the birth of General Electric.

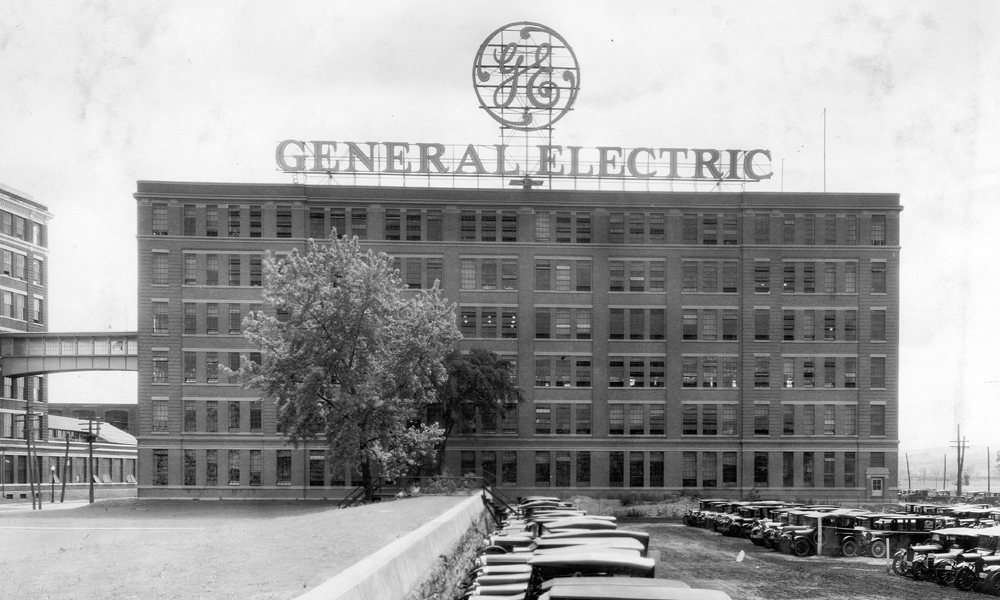

It all started in 1886, when Thomas Edison chose the site of the former McQueen Locomotive in Schenectady as the home base of Edison Machine Works, the company that, by way of an 1892 merger, would become General Electric. Edison himself had sold all of his shares in the company by 1894, but the business he built boomed over the next three-quarters of a century, producing everything from early refrigerators to jet engines. And as it grew, Schenectady, which came to be known as “The City That Lights and Hauls the World” and “The Electric City” because GE and the American Locomotive Company (ALCO) were headquartered there, grew with it. By the early 1940s, the GE workforce in Schenectady had expanded to 45,000 employees, while ALCO boasted 12,000.

Alas, as was the case for countless company towns–those whose success was a direct result of the success of a singular major company (or two) headquartered there–throughout the rust belt, Schenectady’s good fortune didn’t last. Between ALCO shuttering its doors in 1969 and GE laying off a whopping 40,000 Schenectady employees in the second half of the 20th century, Schenectady lost one third of its population—and those people didn’t come back. Add in a nationwide migration to the suburbs and their sprawling shopping malls, and by the 1980s, Schenectady was basically a ghost town. “The Proctors block was decimated,” says Galesi Group’s Buicko. “You could walk down State Street and not get hit by a car because there were no cars on it.” Proctors itself, once a thriving vaudeville theater, had begun showing pornographic films, and by the 1970s had fallen into disrepair and was at risk of being torn down. While a group of concerned citizens banded together to save and restore Proctors, and the theater reopened in 1979, that one victory was no match for the mass layoffs laying waste to the city as a whole.

Schenectady’s next few decades were largely characterized by crime, corruption and blight. “When you’ve got a crack epidemic in the ’90s, and you’ve got a corrupt police department, and you’ve got a school system that’s having trouble with internal staffing problems, you get a lot of newspaper articles that turn people off,” says William Patrick, author of the book Metrofix: The Combative Comeback of a Company Town, which tells the complete story of Schenectady’s rise, fall and rise again and was released in December of last year. (The book was funded by philanthropist Neil Golub.) “So if you live in the Capital Region or close to it, and year after year you read these terrible articles about crime and corruption and school problems, you don’t want to move to the city. So there was a terrible perception problem”—a perception problem that endured well into the 2010s. “When I was in college and I’d tell my parents I was going out in Schenectady, they would be like, ‘Are you sure? That does not seem safe,’” says Ballston Lake native Danielle Walsh, who graduated from SUNY New Paltz in 2015 and eventually moved to Schenectady. “My mom was like, ‘Text me every 20 minutes.’”

But despite what the rest of the Capital Region may have thought, there were some city leaders who had a vision of what Schenectady could still become. One such man was Golub, who at the time was set to take over the Golub Corporation and its Price Chopper supermarket empire from his father. He got together with Roger Hull, then-president of Union College, and economic development manager George Robertson to form Schenectady 2000, a volunteer organization that would clean up the city, at least aesthetically, in the 1990s. “The three of them organized this volunteer force to paint the bridges, add landscaping and change the lighting,” Patrick says. “But they realized, ‘OK, that’s not going to do it. It’s not enough.’ They really needed an independently financed economic development organization.”

Enter the Schenectady Metroplex Development Authority, which is just that: an independently funded public benefit corporation dedicated to the economic development of Downtown Schenectady and its surrounding towns, which was signed into law by former New York State Governor George Pataki in 1998. The only entity of its kind in New York State, Metroplex is actually funded by county sales tax—one half of one percent of the sales tax goes directly to Metroplex for economic development—and has broad power to “design, plan, finance, site, construct, administer, operate, manage and maintain facilities within its service district,” according to its mission statement. In practice, that means Metroplex is involved in pretty much every development project and business opening that happens in Schenectady, period. And that gives the Electric City a major edge—and helps explain why “everything” seems to be opening there.

Today, Metroplex is a bona fide force, but its efforts weren’t immediately felt; even though the city was on the up and up following the authority’s formation, it would take years before the public’s perception of Schenectady began to shift—just ask Walsh’s mom, who eventually did stop asking her adult daughter to excessively text her that she was safe. Something that aided in that shift? Philip Morris’ arrival at Proctors in 2002. “He realized that Proctors wasn’t going to be able to compete, unless they did a really major fundraising campaign,” Patrick says. “Because a bunch of big Broadway shows needed to have a larger stage and a larger space behind the stage.” Under Morris’ leadership as executive director, Proctors raised $40 million to expanded its physical space in 2005 and 2006 so that it could accommodate crowd-pleasing hits such as Phantom of the Opera and Wicked and, more recently, Hamilton, Dear Evan Hansen and the upcoming Hadestown.

Meanwhile, Metroplex had hired Ray Gillen, formerly an economic developer for the state, as its chairman. “When I came in 2004, Schenectady had arguably the most distressed downtown in the state and a dysfunctional economic development system,” Gillen says. “Thirty different groups in the city were involved in one way or another with economic development. When the leadership in the community changed at the county and city levels in 2004, they unified that from dozens of organizations to a unified economic development team.” In other words, from there on out, Metroplex was a one-stop shop for all things economic development. “We’re a single point of contact,” Gillen continues. “You don’t have to talk to dozens of people to get a project approved in Schenectady.”

“The approval process to get projects done here is very streamlined,” adds Buicko, who has worked with Metroplex on most of Galesi’s projects, including Center City, Bow Tie Cinemas and the $500 million Mohawk Harbor project. “You have a quarterback in Ray Gillen and Jayme Lahut.” (Lahut is the authority’s executive director.) Kaytrin Ziemann, co-owner of State Street hotspot The Nest, agrees: “They were amazing,” she says of working with Metroplex to open her restaurant in 2020. “Any road block I ran into, Ray Gillen was all about helping me. Down in City Hall, they step-by-step held my hand. They were so eager for us to

get open.”

While Metroplex is like a quarterback on one hand, it’s like a cheerleader on the other, touting Schenectady whenever possible. A recent example is when entertainment producer Exhibition Hub came looking for an upstate locale for its uber-popular traveling exhibit, Van Gogh: The Immersive Experience, which sold out in huge cities such as LA, Toronto and Chicago. “When people come to us and say ‘We’re looking for a spot,’ we’re very aggressive,” Gillen says. “We met them [at the Schenectady Armory] and showed them the property. We move quickly as an economic development organization.” Metroplex’s pitch as to why Exhibition Hub should choose Schenectady as its host? “Proctors is a big entertainment venue, so people come here for the arts already,” Gillen says. “We have the casino, which is the most visited destination in the Capital Region. We talked about Frog Alley, the college, parking, the kind of support we can give them…it’s right off the highway. We were able to create a pitch that helped them see the advantages of Schenectady.”(One blight though: Someone didn’t think Schenectady was a big enough name, so the sign at the Armory, the digital ads for tickets, and even the listing on the official website all say “Van Gogh Albany.”

Baby steps.)

Another example of Metroplex’s outsized influence came when MVP Healthcare was looking for a place to build its headquarters. While a more suburban area may have been an easier choice given the ample surface parking opportunities, Metroplex helped subsidize a Downtown Schenectady parking garage to mitigate MVP’s costs and level the playing field. In the end, MVP chose Schenectady.

If you haven’t noticed, the benefits of Metroplex and Schenectady’s economic development as a whole are compounding: Investing in one area brings more business and therefore more sales tax to the city, which gives Metroplex more money and more leverage to win over potential investors. By investing in MVP’s parking garage, Metroplex brought more people to downtown—people that need places to eat, shop and live. It’s projects like those that encourage the development of apartment buildings, such as Mill Artisan on lower State Street, and restaurants such as vegan cafe Take Two and the newest venture from the owners of The Nest, Mediterranean restaurant Mila, coming soon to downtown. “During the day, we have lots of large parties during lunch,” Ziemann says of the crowd at The Nest. “GE office lunch, Metroplex comes down, the MVP building, the courthouse—lots of lunch meetings.”

Given the fact that Metroplex is self-perpetuating, development and therefore tourism in Schenectady have only picked up speed, though COVID did set everyone back a bit, what with Proctors and Rivers Casino being closed. On the development side, Mohawk Harbor is an obvious transformation. “When you came across Freemans Bridge and you looked at a bunch of closed-down factories and ugly buildings that were falling apart, it was embarrassing,” Buicko says of the waterfront property that actually used to be home to the aforementioned ALCO. Now, that abandoned 60 acres has been transformed into a state-of-the-art compound boasting an expansive casino, two hotels, restaurants, offices, stores and a concert venue, and is the proposed home of an ice rink that could play host to Union College’s men’s and women’s home hockey games. “We treat it as a place where you can live, work and play all in one,” Buicko says of the area. “And with the price of gas right now, if people can walk or have a short drive to work, the economics are terrific.”

On the tourism side, this year is on track to be unparalleled, what with Van Gogh; Proctors’ upcoming show schedule (Hairspray, Disney’s Aladdin, Hamilton, etc.) and first-ever Fandom Fest (a comic con of sorts); The Alice in Wonderland Experience (an immersive escape room–style team event coming to the city October 1); and the always-popular SummerNight concert (the headliner for the July 22 event had yet to be announced at press time). In addition to what Discover Schenectady’s Todd Garofano calls “the usual suspects” that bring in tourists—Proctors and Rivers Casino, mainly—outdoor recreation in Schenectady has also been booming. “What we’ve seen coming out of the pandemic is that outdoor attractions are doing really well,” he says. “We geofence certain neighborhoods and attractions around Schenectady County to track where the tourists are, and the top five consistently have been Mohawk Harbor/Rivers, Central Park, Freedom Park, Jay Street Marketplace and the Stockade.” The city and county’s offerings are so diverse in fact, that when asked if “The Electric City” was still a fitting nickname for Schenectady, Garofano laughed. “It’s kind of funny,” he says. “We were looking at doing a little brand refresh, and somebody came up with a play on words and called it ‘The Eclectic City.’ And we said, ‘Gee, it kind of makes sense.’” Buicko has recognized the city’s move away from its industrial/electric roots as well. “Schenectady,” he says, “is actually a very good case study on how to reinvent a city.”

That reinvention has made Schenectady such a happening place that it’s drawing in young people—young people who weren’t even alive for Schenectady’s so-called glory days. “We moved in two or three weeks before SummerNight 2019,” says Walsh, the one with the once-worried mother. “We walked outside and it was a madhouse. It was just so awesome to be so centrally located and be able to go to the farmers’ market, get coffee, go to the movies, go out to dinner.” Ziemann felt the draw of Schenectady too, even before opening her first restaurant there. “We had been eyeing State Street for years,” she says. “We had been dying to get down there because of Proctors, the casino, all these apartments going up. It’s kind of like a rebirth in Schenectady and we wanted to be a part of it—big time.”

Obviously, Metroplex is largely responsible for what Ziemann calls Schenectady’s rebirth. But it’s not the whole story. “Put Metroplex aside for a second,” Buicko says. “You had community leaders that really wanted Schenectady to win.” Buicko’s talking about the Neil Golubs of Schenectady—the CEOs of Price Chopper, MVP and location intelligence software company Transfinder that decided to put their headquarters in Schenectady, even when it might have been easier to put them elsewhere. But that mindset extends beyond the city’s corporate and philanthropic leaders to the regular people. “I may have shared with my Schenectady friends, ‘Oh, it’s been sad to see some things aren’t what they used to be in Schenectady,’” says Gallagher, who is employed by Price Chopper, of the city’s darker years. “But I don’t want to hear outsiders say it. I don’t want to listen to people who have lived their whole life in the suburbs trash Schenectady. I still have that pride, and I still try to support it where I can. For me, it’s going to the movies at Bow Tie, grabbing a bite to eat downtown—stuff like that.”

And Gallagher’s not alone. “There aren’t a lot of cities that pull together the way Schenectady does,” Patrick says. “It’s unusual in that sense. I’ve never lived in a place where people are, first of all, so friendly, and second of all, so volunteer oriented. It’s kind of remarkable. Everybody pitches in in this city.”

Under existing legislation, Metroplex is set to lose its sales tax share—a.k.a. go away—in 2038. But if history is any indication, Schenectady civic pride will continue long after that sunset date. And if hard times ever befall Schenectady again in the future, you can bet there will be someone—more like thousands of someones—ready to reinvent the Electric City once again.

To view the story on the Capital Region Living website, click here.